Global markets give you access to new customers. All you need to do is inform potential buyers about your product or service.

Your website is a good place to introduce your product or service outside your locale. Localizing your web content sounds like the right way to reach out to the global market. Localization will bridge the language barriers, or the wider scope of differing cultures.

Before we move on further with the discussion, let’s focus on the definition of “localization.”

What is localization?

According to the Cambridge Dictionary, localization (as a marketing term) is “the process of making a product or service more suitable for a particular country, area, etc.,” while translation is “something that is translated, or the process of translating something, from one language to another.”

In practice, the difference can be a little blurred. While it’s true that localization includes both language and non-language aspects, most cultural adjustments in the localization process are done through the language. Hence, the two terms are often interchangeable.

Good translators will not simply find an equivalent of a word in another language. They will actively research their materials and have an in-depth understanding of the languages they work in.

Depending on the situation, they may or may not convert measurement units and date formats. Technical guide books may need accurate unit conversion, but changing “Fahrenheit 451” to “Celsius 233” would be simply awkward. A good translator will suggest what to change and what to leave as it is.

Some people call this conversion process “localization.” The truth is, unit conversions had become a part of translation, long before the word “localization” was used to describe the process.

When we talk about linguistic versus non-linguistic aspects of a medium, and view them as separate entities, localization and translation may look different. However, when we look at the whole process of translating the message, seeing both elements as translatable items, the terms are interchangeable.

In this article, the terms “localization” and “translation” will be used interchangeably. We are going to discuss how to use a website as a communication tool to gain a new market in different cultures.

Localization: who is it for?

A good localization is not cheap, so it would be wise to ask yourselves several questions beforehand:

- Who is your audience?

- What kind of culture do they live in?

- What kind of problems may arise during the localization process?

I will explain the details below.

Who is your ideal audience?

Knowing your target audience should be at the top of your business plan.

For some, localization is not needed because they live in the same region and speak the same language as their target market. For example, daycare services, local coffee shops, and restaurants.

In some cases, people who live in the same region may speak different languages. In a bilingual society, you may want to cater to speakers of both languages as a sign of respect. In a multilingual society, aim to translate to the lingua franca and/or the language used by the majority. It makes people feel seen and it can create a positive image to your brand.

Sometimes, website translation is required by law. In Quebec, for instance, where French is spoken as the provincial language, you’ll need to include a French version of your website. You may also want to check other types of linguistic experiences you need to provide.

If your target market lives across the sea and speaks a different language, you may not have any choice but to localize. However, if those people can speak your language, consider other aspects (cultural and/or legal) to make an informed decision on whether to translate.

Although there are many benefits of website translation, you don’t always have to do it now. Especially when your budget is tight or you can spend it on something more urgent. It’s better to postpone than to have a badly translated website. The price of cheap translation is costly.

If you’re legally required to launch a bilingual website but you don’t have the budget, you may want to check if you can be exempted. If you are not exempted, hire volunteers or seek government support, if possible.

Unless required otherwise by law, there is nothing wrong with using your current language in your product or service. You can maintain the already-formed relationship by focusing on what you have in common: the same interest.

Understanding cultural and linguistic intricacies

For example, you have a coding tutorial website. Your current audience is IT professionals—mostly college graduates. You see an opportunity to expand to India.

Localization is unlikely to be needed in this case, as most Indian engineers have a good grasp of English. So, instead of doing a web translation project, you can use your money to improve or develop a new product or service for your Indian audience. Maybe you want to set up a workshop or a meetup in India. Or a bootcamp retreat in the country.

You can achieve this by focusing on the similarities you have with your audience.

The same rule applies to other countries where English language is commonly used by IT professionals. In the developing world, where English is rarely used, some self-taught programmers become “good hackers” to earn some money. You may wonder how, despite their lack of English skill, they can learn programming.

There’s an explanation for it.

There are two types of language skills: passive (listening, reading) and active (speaking, writing). Passive language skills are usually learned first. Active language skills are developed later. You learn to speak by listening, and learn to write by reading. You go through this process as a child and, again, when you learn a new language as an adult. (This is not to confuse language acquisition with language learning, but to note that the process is relatively the same.)

As most free IT course materials are available online in English, some programmers may have to adapt and study English (passively) as they go. They may not be considered “fluent” in a formal way, but it doesn’t mean they lack the ability to grasp the language. They may not be able to speak or write perfectly, but they can understand technical texts.

In short, passive and active language skills can grow at different speeds. This fact leads you to a new group of potential audience: those who can understand English, but only passively.

If your product is in a text format, translation won’t be necessary for this type of audience. If it’s an audio or video format, you may need to add subtitles, since native English speakers speak in so many different accents and at various speeds. Captioning will also help the hard of hearing. It may be required by regional or national accessibility legislation too. And it’s the right thing to do.

One might argue that if these people can understand English, they will understand the text better in their native tongue.

Well, if all the programs you’re using or referring to are available in their native language version, it may not be a problem. But in reality, this is often not the case.

Linguistic consistency helps programmers work faster. And this alone should trump the presumed ease that comes with translation.

Some problems with localization

I was once involved in a global internet company’s localization project in Indonesia.

Indonesian SMEs mostly speak Indonesian since they mainly serve the domestic market. So, it was the right decision to target Indonesian SMEs using Indonesian language.

The company had the budget to target Indonesia’s market of 58 million SMEs, and there weren’t too many competitors yet. I think the localization plan was justified. But even with this generally well-thought-out plan, there were some problems in its execution.

The materials were filled with jargon and annoying outlinks. You could not just read an instruction until it was completed, because after a few words, you would be confronted with a “smart term.” Now to understand this smart term, you would have to follow a link that would take you to a separate page that was supposed to explain everything, but in that page you would find more smart terms that you’d need to click. At this point, the scent of information would have grown cold, and you’d likely have forgotten what you were reading or why.

Small business owners are among the busiest folks you can find. They do almost everything by themselves. They would not waste their time trying to read pages of instructions that throw them right and left.

Language-wise, the instructions could have been simplified. Design-wise, a hover/focus pop-up containing a brief definition or description could have been used to explain special terms.

I agree pop-ups can be distracting, but in terms of ease, for this use case, they would have worked far better than outlinks. There are some ways to improve hover/focus pop-ups to make them more readable.

Ho

Recommended Story For You :

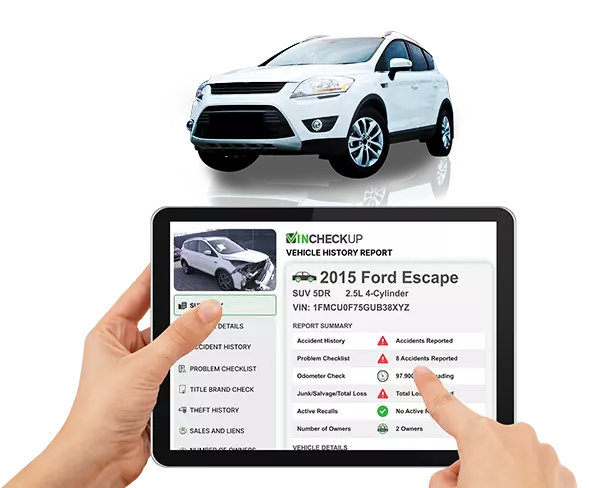

GET YOUR VINCHECKUP REPORT

The Future Of Marketing Is Here

Images Aren’t Good Enough For Your Audience Today!

Last copies left! Hurry up!

GET THIS WORLD CLASS FOREX SYSTEM WITH AMAZING 40+ RECOVERY FACTOR

Browse FREE CALENDARS AND PLANNERS

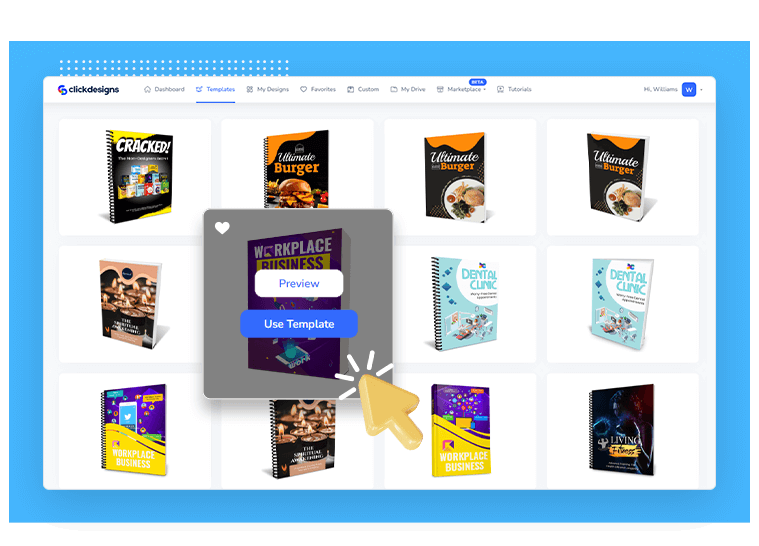

Creates Beautiful & Amazing Graphics In MINUTES

Uninstall any Unwanted Program out of the Box

Did you know that you can try our Forex Robots for free?